Editorial: Extradition, an unending debate

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar rightly described it as a big step in ensuring justice for the victims of the 26/11 attacks.

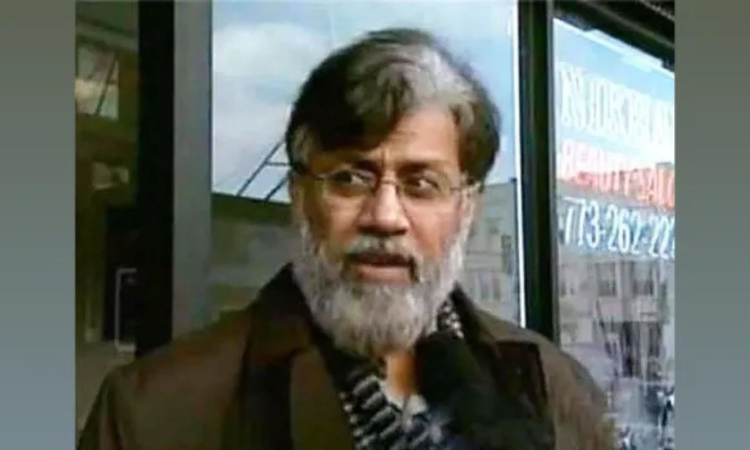

Tahawwur Hussain Rana

India scored an important victory with the extradition of Tahawwur Hussain Rana, one of the key accused in the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks, from the US after a prolonged legal battle which tested India’s perseverance and strategy.

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar rightly described it as a big step in ensuring justice for the victims of the 26/11 attacks.

Close on the heels of the Rana extradition comes the news about the arrest of fugitive billionaire jeweller Mehul Choksi, who is wanted in connection with the multi-crore Punjab National Bank scam, in Belgium and the prospect of his extradition to India.

It may be noted here that even the extradition of persons accused of crimes, especially of terrorist nature, often proves daunting and time-consuming when they are in Western countries.

In this context, one could recall the extradition of gangster Abul Salem from Portugal. It gets even more difficult in cases relating to financial scams.

Despite India’s efforts, other billionaires Vijay Mallya, Lalit Modi and Nirav Modi continue to put legal hurdles and evade extradition to India where they are wanted in financial cases is a case in point.

The government has been facing innumerable challenges with regard to extradition to India.

Data indicates a relatively lower success rate as many requests are yet to be fulfilled, despite having signed treaties with 48 countries.

For instance, in December 2024 the Union Home Ministry informed Lok Sabha that 65 extradition requests are under consideration of USA authorities.

As extradition involved two nations, it is obvious that there will be procedural issues which often vary from one another.

Moreover, in any country, judicial process requires rigorous process in establishment of prima facie case backed by strong legally tenable evidence.

Even after extradition, treaty clauses or judge’s order could limit the scope of prosecution.

Secondly, much depends not only regarding the existence of an extradition treaty but also on the bilateral ties between the two countries. Here again India’s diplomatic relations helps in some instances and in other instances it needs to up the game. Thirdly, the biggest hurdle is the political dimension of extradition. If a court in a western country suspects political motives or persecution leading to violation of fair justice behind the extradition request, it will exercise what may seem like extreme caution and reluctance.

Most fugitives try to use this aspect in delaying extradition process. To be fair, it cuts both ways. India has the Extradition Act to deal with requests made and received by India.

Two extradition cases which drew global attention were the Bangladesh seeking the extradition of Sheikh Hasina and US reportedly eyeing the extradition of a former intelligence officer who is named in an US indictment in a case relating to a foiled attempt to assassinate a US citizen and widely known to be a Sikh separatist leader.

India has an evolved policy on extradition requests made to it and it goes extra mile to ensure that its stand is in line with international principles governing extradition – especially the principle of dual criminality (should be a crime in both countries) and fair trial whereby the person is guaranteed to receive fair trial.

India needs to have a calibrated and measured response which is based on sound legal reasoning and in sync with international law so that it helps strengthen the case of India’s own extradition requests made to other countries. After all, in international relations, matters are often decided on the principle of mutual agreement and cooperation with a dash of pragmatism thrown in.