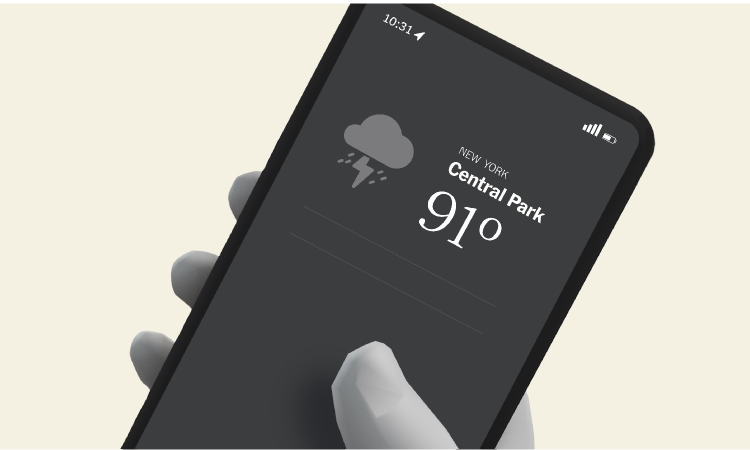

How your phone gets the weather

You’re in New York City’s Central Park, planning your weekend. Will it be sunny and warm? The answer is based on a trove of measurements taken at places near and far — from a local weather station, all the way to outer space.

We depend on weather predictions not just to dress for work or plan trips. Businesses use forecasts to prepare for storms, fly planes, build houses and deliver mail. The more weather observations meteorologists can rely on, the more precise their forecasts will be. Here’s what goes into an accurate forecast.

You’re in New York City’s Central Park, planning your weekend. Will it be sunny and warm? The answer is based on a trove of measurements taken at places near and far — from a local weather station, all the way to outer space.

Half a mile away, the station at Belvedere Castle measures the air’s warmth and humidity, like more than 900 other US stations that continuously collect data.

Across the river to the east, a plane takes off from LaGuardia Airport. Instruments on board will measure the atmosphere along the plane’s route. The U.S. government purchases this data from private aircraft carriers.

Twenty miles away, off the Jersey shore in the Atlantic, a buoy bobs along, recording the height of the waves, the temperature of the water and changes in the atmosphere. It is one of 200 buoys that help predict extreme weather with accuracy.

Back on land on Long Island, a radar sends rays of energy that bounce off rain droplets and send back data about their direction and speed. This is how we know whether it’s going to rain in the next hour.

Miles above the radar, a balloon rises into the stratosphere to capture readings of temperature, humidity and wind. Balloons are crucial to understanding where storms form.

At the edge of space, constellations of satellites constantly capture and send data back to Earth, helping create a complete picture of weather around the world. Satellites eventually reach the end of their life span, and, once they do, they need to be replaced to keep weather models accurate.

All these measurements from land, sea and space now flow to a supercomputer in Virginia. Here, machine-generated predictions, fine-tuned by scientists, go out to a network of local offices and private companies.

Private companies including AccuWeather, The Weather Co., Google and Apple interpret and customize this public data for their apps. The forecast pops up on your phone, in Central Park.

Government cuts have forced nearly 600 layoffs and early retirements at the National Weather Service this year. This means fewer people will be available to process the data and maintain equipment like radars — an already crumbling infrastructure from the 1990s. Some local offices, such as the one in Goodland, Kan., had to suspend work during nighttime.

Less data is being collected. Because of staff shortages, some local offices have reduced the frequency of balloon launches.

Some experts think that the lack of such data collection could already be undermining the accuracy of long-range weather prediction models.

“We’re penalizing ourselves every time we reduce the observations,” said Joe Friday, who was the weather service director from 1988 to 1997.

Other experts are less certain about the effect on current forecasts. They all agree that scientists working on models want more data, not less.

The weather service is still assessing the impact of having less data from balloon launches on the forecast.

“Fully understanding these impacts would require much longer studies,” said a spokesperson, Marissa Anderson.

Each US taxpayer spends about $4 per year to cover the weather service budget, which Friday says is a small cost compared with the benefits.

“Weather service is one of those governmental functions that protects every man, woman and child in this country,” he said. “I only hope that the present government leadership will understand the necessity of continuing to improve this vital service.”

c.2025 The New York Times Company