The life of a showgirl: Taylor-ing Swift success – no matter what music sounds like

In recent years, Swift has been criticised for releasing multiple limited editions of her albums, and The Life of a Showgirl is no exception

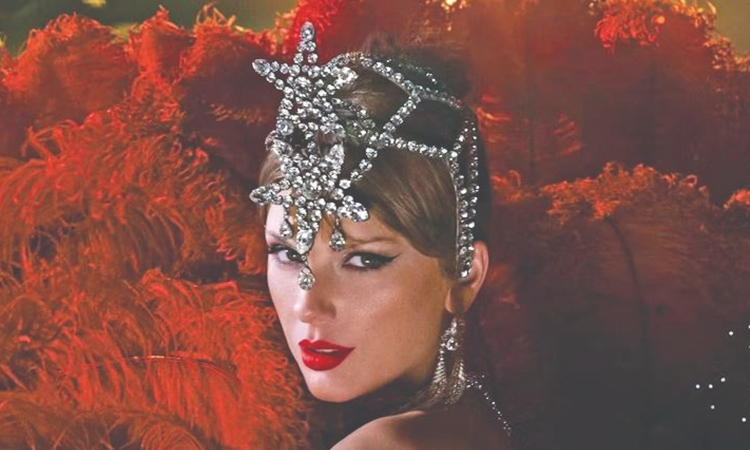

Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift’s new album The Life of a Showgirl has been released to much fanfare. While reviews range from flop to masterpiece, it is almost certain to dominate global charts this week thanks to a meticulously planned marketing campaign.

Swift is a global phenomenon and, as a lecturer in marketing, business and society, I am one of many researchers exploring the social science of her success.

In recent years, Swift has been criticised for releasing multiple limited editions of her albums, and The Life of a Showgirl is no exception. At the time of writing, over 24 different versions of the CD and vinyl have been released, featuring alternate covers, coloured vinyls, signed editions, and CDs with exclusive tracks unavailable on streaming platforms.

This strategy is a powerful tool for chart success, where every physical purchase, regardless of variant, counts. Many editions are released in timed drops on Swift’s website, available only for 48 hours or until stock runs out. This creates a sense of scarcity and urgency among fans, driving impulsive purchases for fear of missing out on their “favourite variant.”

Research shows that such marketing tactics can cause stress and anxiety, particularly among neurodivergent fans. A thriving secondary market exploits this demand, with resellers inflating prices for rare versions. Many fans spend far more than expected chasing exclusivity.

This manipulation of charts through product proliferation is a privilege only artists with immense resources can afford. Vinyl pressings are expensive, and few can match Swift’s scale. The materials used to produce vinyl are also environmentally unsustainable. Although Swift claims to offset her travel emissions, she has not yet adopted eco-friendly album formats. Regardless of the financial or ecological toll, these tactics remain highly effective for chart dominance.

Unlike most artists, Swift rarely releases a lead single to promote an upcoming album. All pre-release information comes directly from her team under strict secrecy. What might hinder others instead heightens intrigue for Swift, ensuring everyone hears the album simultaneously and minimising leaks or early criticism that could dampen sales.

However, this control can hurt smaller retailers. Independent record stores planning midnight launches often cancel events when embargoed shipments arrive late. Still, the secrecy lets Swift orchestrate the narrative entirely, using puzzles, easter eggs, and cryptic teasers to keep social media engagement high.

Over release weekend, Swift hosted global cinema “launch parties,” where fans previewed the Fate of Ophelia video and behind-the-scenes commentary. Beyond advertising, these screenings created exclusive communal experiences for “Swifties,” echoing the collective energy seen during the Eras Tour. Once informal fan gatherings, such events have become lucrative marketing moments, generating both revenue and online buzz.

Unsurprisingly, few artists release music near Swift’s drop dates. Competing even weeks later can be futile—Billie Eilish, for instance, saw her album dethroned five weeks post-release when Swift issued three new Tortured Poets Department editions.

It is increasingly difficult for artists to rival such a force. Swift and her fanbase wield enough influence to dominate charts at will, raising pressing questions about the state of today’s music industry. What do artists owe their fans? Is this model sustainable amid a climate emergency? Should consumers be protected from manipulative marketing? Researchers across business, marketing, and corporate responsibility have debated such questions for decades. But as Swift reshapes industry norms, it is vital that fans, artists, and executives together consider what a fairer, more sustainable music economy might look like.

The Conversation